For the last 40 years, BM25 has served as the standard for search engines. It is a simple yet powerful algorithm that has been used by many search engines, including Google, Bing, and Yahoo.

Though it seemed that the advent of vector search would diminish its influence, it did so only partially. The current state-of-the-art approach to retrieval nowadays tries to incorporate BM25 along with embeddings into a hybrid search system.

However, the use case of text retrieval has significantly shifted since the introduction of RAG. Many assumptions upon which BM25 was built are no longer valid.

For example, the typical length of documents and queries vary significantly between traditional web search and modern RAG systems.

In this article, we will recap what made BM25 relevant for so long and why alternatives have struggled to replace it. Finally, we will discuss BM42, as the next step in the evolution of lexical search.

Why has BM25 stayed relevant for so long?

To understand why, we need to analyze its components.

The famous BM25 formula is defined as:

Let’s simplify this to gain a better understanding.

The

The

The

It is fair to say that the IDF is the most important part of the BM25 formula.

IDF selects the most important terms in the query relative to the specific document collection.

So intuitively, we can interpret the IDF as term importance within the corpora.

That explains why BM25 is so good at handling queries, which dense embeddings consider out-of-domain.

The last component of the formula can be intuitively interpreted as term importance within the document. This might look a bit complicated, so let’s break it down.

- The

- The

- The

Will BM25 term importance in the document work for RAG?

As we can see, the term importance in the document heavily depends on the statistics within the document. Moreover, statistics works well if the document is long enough. Therefore, it is suitable for searching webpages, books, articles, etc.

However, would it work as well for modern search applications, such as RAG? Let’s see.

The typical length of a document in RAG is much shorter than that of web search. In fact, even if we are working with webpages and articles, we would prefer to split them into chunks so that a) Dense models can handle them and b) We can pinpoint the exact part of the document which is relevant to the query

As a result, the document size in RAG is small and fixed.

That effectively renders the term importance in the document part of the BM25 formula useless. The term frequency in the document is always 0 or 1, and the relative length of the document is always 1.

So, the only part of the BM25 formula that is still relevant for RAG is IDF. Let’s see how we can leverage it.

Why SPLADE is not always the answer

Before discussing our new approach, let’s examine the current state-of-the-art alternative to BM25 - SPLADE.

The idea behind SPLADE is interesting—what if we let a smart, end-to-end trained model generate a bag-of-words representation of the text for us? It will assign all the weights to the tokens, so we won’t need to bother with statistics and hyperparameters. The documents are then represented as a sparse embedding, where each token is represented as an element of the sparse vector.

And it works in academic benchmarks. Many papers report that SPLADE outperforms BM25 in terms of retrieval quality. This performance, however, comes at a cost.

Inappropriate Tokenizer: To incorporate transformers for this task, SPLADE models require using a standard transformer tokenizer. These tokenizers are not designed for retrieval tasks. For example, if the word is not in the (quite limited) vocabulary, it will be either split into subwords or replaced with a

[UNK]token. This behavior works well for language modeling but is completely destructive for retrieval tasks.Expensive Token Expansion: In order to compensate the tokenization issues, SPLADE uses token expansion technique. This means that we generate a set of similar tokens for each token in the query. There are a few problems with this approach:

- It is computationally and memory expensive. We need to generate more values for each token in the document, which increases both the storage size and retrieval time.

- It is not always clear where to stop with the token expansion. The more tokens we generate, the more likely we are to get the relevant one. But simultaneously, the more tokens we generate, the more likely we are to get irrelevant results.

- Token expansion dilutes the interpretability of the search. We can’t say which tokens were used in the document and which were generated by the token expansion.

Domain and Language Dependency: SPLADE models are trained on specific corpora. This means that they are not always generalizable to new or rare domains. As they don’t use any statistics from the corpora, they cannot adapt to the new domain without fine-tuning.

Inference Time: Additionally, currently available SPLADE models are quite big and slow. They usually require a GPU to make the inference in a reasonable time.

At Qdrant, we acknowledge the aforementioned problems and are looking for a solution. Our idea was to combine the best of both worlds - the simplicity and interpretability of BM25 and the intelligence of transformers while avoiding the pitfalls of SPLADE.

And here is what we came up with.

The best of both worlds

As previously mentioned, IDF is the most important part of the BM25 formula. In fact it is so important, that we decided to build its calculation into the Qdrant engine itself.

Check out our latest release notes. This type of separation allows streaming updates of the sparse embeddings while keeping the IDF calculation up-to-date.

As for the second part of the formula, the term importance within the document needs to be rethought.

Since we can’t rely on the statistics within the document, we can try to use the semantics of the document instead. And semantics is what transformers are good at. Therefore, we only need to solve two problems:

- How does one extract the importance information from the transformer?

- How can tokenization issues be avoided?

Attention is all you need

Transformer models, even those used to generate embeddings, generate a bunch of different outputs. Some of those outputs are used to generate embeddings.

Others are used to solve other kinds of tasks, such as classification, text generation, etc.

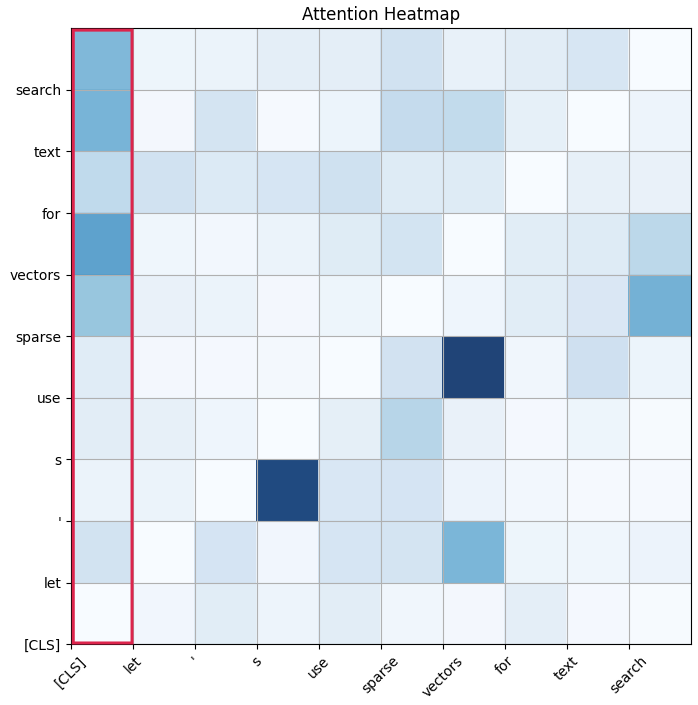

The one particularly interesting output for us is the attention matrix.

Attention matrix

The attention matrix is a square matrix, where each row and column corresponds to the token in the input sequence. It represents the importance of each token in the input sequence for each other.

The classical transformer models are trained to predict masked tokens in the context, so the attention weights define which context tokens influence the masked token most.

Apart from regular text tokens, the transformer model also has a special token called [CLS]. This token represents the whole sequence in the classification tasks, which is exactly what we need.

By looking at the attention row for the [CLS] token, we can get the importance of each token in the document for the whole document.

sentences = "Hello, World - is the starting point in most programming languages"

features = transformer.tokenize(sentences)

# ...

attentions = transformer.auto_model(**features, output_attentions=True).attentions

weights = torch.mean(attentions[-1][0,:,0], axis=0)

# ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲

# │ │ │ └─── [CLS] token is the first one

# │ │ └─────── First item of the batch

# │ └────────── Last transformer layer

# └────────────────────────── Average all 6 attention heads

for weight, token in zip(weights, tokens):

print(f"{token}: {weight}")

# [CLS] : 0.434 // Filter out the [CLS] token

# hello : 0.039

# , : 0.039

# world : 0.107 // <-- The most important token

# - : 0.033

# is : 0.024

# the : 0.031

# starting : 0.054

# point : 0.028

# in : 0.018

# most : 0.016

# programming : 0.060 // <-- The third most important token

# languages : 0.062 // <-- The second most important token

# [SEP] : 0.047 // Filter out the [SEP] token

The resulting formula for the BM42 score would look like this:

Note that classical transformers have multiple attention heads, so we can get multiple importance vectors for the same document. The simplest way to combine them is to simply average them.

These averaged attention vectors make up the importance information we were looking for. The best part is, one can get them from any transformer model, without any additional training. Therefore, BM42 can support any natural language as long as there is a transformer model for it.

In our implementation, we use the sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model, which gives a huge boost in the inference speed compared to the SPLADE models. In practice, any transformer model can be used.

It doesn’t require any additional training, and can be easily adapted to work as BM42 backend.

WordPiece retokenization

The final piece of the puzzle we need to solve is the tokenization issue. In order to get attention vectors, we need to use native transformer tokenization. But this tokenization is not suitable for the retrieval tasks. What can we do about it?

Actually, the solution we came up with is quite simple. We reverse the tokenization process after we get the attention vectors.

Transformers use WordPiece tokenization. In case it sees the word, which is not in the vocabulary, it splits it into subwords.

Here is how that looks:

"unbelievable" -> ["un", "##believ", "##able"]

What can merge the subwords back into the words. Luckily, the subwords are marked with the ## prefix, so we can easily detect them.

Since the attention weights are normalized, we can simply sum the attention weights of the subwords to get the attention weight of the word.

After that, we can apply the same traditional NLP techniques, as

- Removing of the stop-words

- Removing of the punctuation

- Lemmatization

In this way, we can significantly reduce the number of tokens, and therefore minimize the memory footprint of the sparse embeddings. We won’t simultaneously compromise the ability to match (almost) exact tokens.

Practical examples

| Trait | BM25 | SPLADE | BM42 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | High ✅ | Ok 🆗 | High ✅ |

| Document Inference speed | Very high ✅ | Slow 🐌 | High ✅ |

| Query Inference speed | Very high ✅ | Slow 🐌 | Very high ✅ |

| Memory footprint | Low ✅ | High ❌ | Low ✅ |

| In-domain accuracy | Ok 🆗 | High ✅ | High ✅ |

| Out-of-domain accuracy | Ok 🆗 | Low ❌ | Ok 🆗 |

| Small documents accuracy | Low ❌ | High ✅ | High ✅ |

| Large documents accuracy | High ✅ | Low ❌ | Ok 🆗 |

| Unknown tokens handling | Yes ✅ | Bad ❌ | Yes ✅ |

| Multi-lingual support | Yes ✅ | No ❌ | Yes ✅ |

| Best Match | Yes ✅ | No ❌ | Yes ✅ |

Starting from Qdrant v1.10.0, BM42 can be used in Qdrant via FastEmbed inference.

Let’s see how you can setup a collection for hybrid search with BM42 and jina.ai dense embeddings.

PUT collections/my-hybrid-collection

{

"vectors": {

"jina": {

"size": 768,

"distance": "Cosine"

}

},

"sparse_vectors": {

"bm42": {

"modifier": "idf" // <--- This parameter enables the IDF calculation

}

}

}

from qdrant_client import QdrantClient, models

client = QdrantClient()

client.create_collection(

collection_name="my-hybrid-collection",

vectors_config={

"jina": models.VectorParams(

size=768,

distance=models.Distance.COSINE,

)

},

sparse_vectors_config={

"bm42": models.SparseVectorParams(

modifier=models.Modifier.IDF,

)

}

)

The search query will retrieve the documents with both dense and sparse embeddings and combine the scores using the Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) algorithm.

from fastembed import SparseTextEmbedding, TextEmbedding

query_text = "best programming language for beginners?"

model_bm42 = SparseTextEmbedding(model_name="Qdrant/bm42-all-minilm-l6-v2-attentions")

model_jina = TextEmbedding(model_name="jinaai/jina-embeddings-v2-base-en")

sparse_embedding = list(model_bm42.query_embed(query_text))[0]

dense_embedding = list(model_jina.query_embed(query_text))[0]

client.query_points(

collection_name="my-hybrid-collection",

prefetch=[

models.Prefetch(query=sparse_embedding.as_object(), using="bm42", limit=10),

models.Prefetch(query=dense_embedding.tolist(), using="jina", limit=10),

],

query=models.FusionQuery(fusion=models.Fusion.RRF), # <--- Combine the scores

limit=10

)

Benchmarks

To prove the point further we have conducted some benchmarks to highlight the cases where BM42 outperforms BM25. Please note, that we didn’t intend to make an exhaustive evaluation, as we are presenting a new approach, not a new model.

For out experiments we choose quora dataset, which represents a question-deduplication task the Question-Answering task.

The typical example of the dataset is the following:

{"_id": "109", "text": "How GST affects the CAs and tax officers?"}

{"_id": "110", "text": "Why can't I do my homework?"}

{"_id": "111", "text": "How difficult is it get into RSI?"}

As you can see, it has pretty short texts, there are not much of the statistics to rely on.

After encoding with BM42, the average vector size is only 5.6 elements per document.

With datatype: uint8 available in Qdrant, the total size of the sparse vector index is about 13MB for ~530k documents.

As a reference point, we use:

- BM25 with tantivy

- the sparse vector BM25 implementation with the same preprocessing pipeline like for BM42: tokenization, stop-words removal, and lemmatization

| BM25 (tantivy) | BM25 (Sparse) | BM42 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recall @ 10 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

* - values were corrected after the publication due to a mistake in the evaluation script.

To make our benchmarks transparent, we have published scripts we used for the evaluation: see github repo.

Please note, that both BM25 and BM42 won’t work well on their own in a production environment. Best results are achieved with a combination of sparse and dense embeddings in a hybrid approach. In this scenario, the two models are complementary to each other. The sparse model is responsible for exact token matching, while the dense model is responsible for semantic matching.

Some more advanced models might outperform default sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model we were using.

We encourage developers involved in training embedding models to include a way to extract attention weights and contribute to the BM42 backend.

Fostering curiosity and experimentation

Despite all of its advantages, BM42 is not always a silver bullet. For large documents without chunks, BM25 might still be a better choice.

There might be a smarter way to extract the importance information from the transformer. There could be a better method to weigh IDF against attention scores.

Qdrant does not specialize in model training. Our core project is the search engine itself. However, we understand that we are not operating in a vacuum. By introducing BM42, we are stepping up to empower our community with novel tools for experimentation.

We truly believe that the sparse vectors method is at exact level of abstraction to yield both powerful and flexible results.

Many of you are sharing your recent Qdrant projects in our Discord channel. Feel free to try out BM42 and let us know what you come up with.