What is a Sparse Vector? How to Achieve Vector-based Hybrid Search

Nirant Kasliwal

·December 09, 2023

Think of a library with a vast index card system. Each index card only has a few keywords marked out (sparse vector) of a large possible set for each book (document). This is what sparse vectors enable for text.

What are sparse and dense vectors?

Sparse vectors are like the Marie Kondo of data—keeping only what sparks joy (or relevance, in this case).

Consider a simplified example of 2 documents, each with 200 words. A dense vector would have several hundred non-zero values, whereas a sparse vector could have, much fewer, say only 20 non-zero values.

In this example: We assume it selects only 2 words or tokens from each document. The rest of the values are zero. This is why it’s called a sparse vector.

dense = [0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, ...] # several hundred floats

sparse = [{331: 0.5}, {14136: 0.7}] # 20 key value pairs

The numbers 331 and 14136 map to specific tokens in the vocabulary e.g. ['chocolate', 'icecream']. The rest of the values are zero. This is why it’s called a sparse vector.

The tokens aren’t always words though, sometimes they can be sub-words: ['ch', 'ocolate'] too.

They’re pivotal in information retrieval, especially in ranking and search systems. BM25, a standard ranking function used by search engines like Elasticsearch, exemplifies this. BM25 calculates the relevance of documents to a given search query.

BM25’s capabilities are well-established, yet it has its limitations.

BM25 relies solely on the frequency of words in a document and does not attempt to comprehend the meaning or the contextual importance of the words. Additionally, it requires the computation of the entire corpus’s statistics in advance, posing a challenge for large datasets.

Sparse vectors harness the power of neural networks to surmount these limitations while retaining the ability to query exact words and phrases. They excel in handling large text data, making them crucial in modern data processing a and marking an advancement over traditional methods such as BM25.

Understanding sparse vectors

Sparse Vectors are a representation where each dimension corresponds to a word or subword, greatly aiding in interpreting document rankings. This clarity is why sparse vectors are essential in modern search and recommendation systems, complimenting the meaning-rich embedding or dense vectors.

Dense vectors from models like OpenAI Ada-002 or Sentence Transformers contain non-zero values for every element. In contrast, sparse vectors focus on relative word weights per document, with most values being zero. This results in a more efficient and interpretable system, especially in text-heavy applications like search.

Sparse Vectors shine in domains and scenarios where many rare keywords or specialized terms are present. For example, in the medical domain, many rare terms are not present in the general vocabulary, so general-purpose dense vectors cannot capture the nuances of the domain.

| Feature | Sparse Vectors | Dense Vectors |

|---|---|---|

| Data Representation | Majority of elements are zero | All elements are non-zero |

| Computational Efficiency | Generally higher, especially in operations involving zero elements | Lower, as operations are performed on all elements |

| Information Density | Less dense, focuses on key features | Highly dense, capturing nuanced relationships |

| Example Applications | Text search, Hybrid search | RAG, many general machine learning tasks |

Where do sparse vectors fail though? They’re not great at capturing nuanced relationships between words. For example, they can’t capture the relationship between “king” and “queen” as well as dense vectors.

SPLADE

Let’s check out SPLADE, an excellent way to make sparse vectors. Let’s look at some numbers first. Higher is better:

| Model | MRR@10 (MS MARCO Dev) | Type |

|---|---|---|

| BM25 | 0.184 | Sparse |

| TCT-ColBERT | 0.359 | Dense |

| doc2query-T5 link | 0.277 | Sparse |

| SPLADE | 0.322 | Sparse |

| SPLADE-max | 0.340 | Sparse |

| SPLADE-doc | 0.322 | Sparse |

| DistilSPLADE-max | 0.368 | Sparse |

All numbers are from SPLADEv2. MRR is Mean Reciprocal Rank, a standard metric for ranking. MS MARCO is a dataset for evaluating ranking and retrieval for passages.

SPLADE is quite flexible as a method, with regularization knobs that can be tuned to obtain different models as well:

SPLADE is more a class of models rather than a model per se: depending on the regularization magnitude, we can obtain different models (from very sparse to models doing intense query/doc expansion) with different properties and performance.

First, let’s look at how to create a sparse vector. Then, we’ll look at the concepts behind SPLADE.

Creating a sparse vector

We’ll explore two different ways to create a sparse vector. The higher performance way to create a sparse vector from dedicated document and query encoders. We’ll look at a simpler approach – here we will use the same model for both document and query. We will get a dictionary of token ids and their corresponding weights for a sample text - representing a document.

If you’d like to follow along, here’s a Colab Notebook, alternate link with all the code.

Setting Up

from transformers import AutoModelForMaskedLM, AutoTokenizer

model_id = "naver/splade-cocondenser-ensembledistil"

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_id)

model = AutoModelForMaskedLM.from_pretrained(model_id)

text = """Arthur Robert Ashe Jr. (July 10, 1943 – February 6, 1993) was an American professional tennis player. He won three Grand Slam titles in singles and two in doubles."""

Computing the sparse vector

import torch

def compute_vector(text):

"""

Computes a vector from logits and attention mask using ReLU, log, and max operations.

"""

tokens = tokenizer(text, return_tensors="pt")

output = model(**tokens)

logits, attention_mask = output.logits, tokens.attention_mask

relu_log = torch.log(1 + torch.relu(logits))

weighted_log = relu_log * attention_mask.unsqueeze(-1)

max_val, _ = torch.max(weighted_log, dim=1)

vec = max_val.squeeze()

return vec, tokens

vec, tokens = compute_vector(text)

print(vec.shape)

You’ll notice that there are 38 tokens in the text based on this tokenizer. This will be different from the number of tokens in the vector. In a TF-IDF, we’d assign weights only to these tokens or words. In SPLADE, we assign weights to all the tokens in the vocabulary using this vector using our learned model.

Term expansion and weights

def extract_and_map_sparse_vector(vector, tokenizer):

"""

Extracts non-zero elements from a given vector and maps these elements to their human-readable tokens using a tokenizer. The function creates and returns a sorted dictionary where keys are the tokens corresponding to non-zero elements in the vector, and values are the weights of these elements, sorted in descending order of weights.

This function is useful in NLP tasks where you need to understand the significance of different tokens based on a model's output vector. It first identifies non-zero values in the vector, maps them to tokens, and sorts them by weight for better interpretability.

Args:

vector (torch.Tensor): A PyTorch tensor from which to extract non-zero elements.

tokenizer: The tokenizer used for tokenization in the model, providing the mapping from tokens to indices.

Returns:

dict: A sorted dictionary mapping human-readable tokens to their corresponding non-zero weights.

"""

# Extract indices and values of non-zero elements in the vector

cols = vector.nonzero().squeeze().cpu().tolist()

weights = vector[cols].cpu().tolist()

# Map indices to tokens and create a dictionary

idx2token = {idx: token for token, idx in tokenizer.get_vocab().items()}

token_weight_dict = {

idx2token[idx]: round(weight, 2) for idx, weight in zip(cols, weights)

}

# Sort the dictionary by weights in descending order

sorted_token_weight_dict = {

k: v

for k, v in sorted(

token_weight_dict.items(), key=lambda item: item[1], reverse=True

)

}

return sorted_token_weight_dict

# Usage example

sorted_tokens = extract_and_map_sparse_vector(vec, tokenizer)

sorted_tokens

There will be 102 sorted tokens in total. This has expanded to include tokens that weren’t in the original text. This is the term expansion we will talk about next.

Here are some terms that are added: “Berlin”, and “founder” - despite having no mention of Arthur’s race (which leads to Owen’s Berlin win) and his work as the founder of Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health. Here are the top few sorted_tokens with a weight of more than 1:

{

"ashe": 2.95,

"arthur": 2.61,

"tennis": 2.22,

"robert": 1.74,

"jr": 1.55,

"he": 1.39,

"founder": 1.36,

"doubles": 1.24,

"won": 1.22,

"slam": 1.22,

"died": 1.19,

"singles": 1.1,

"was": 1.07,

"player": 1.06,

"titles": 0.99,

...

}

If you’re interested in using the higher-performance approach, check out the following models:

Why SPLADE works: term expansion

Consider a query “solar energy advantages”. SPLADE might expand this to include terms like “renewable,” “sustainable,” and “photovoltaic,” which are contextually relevant but not explicitly mentioned. This process is called term expansion, and it’s a key component of SPLADE.

SPLADE learns the query/document expansion to include other relevant terms. This is a crucial advantage over other sparse methods which include the exact word, but completely miss the contextually relevant ones.

This expansion has a direct relationship with what we can control when making a SPLADE model: Sparsity via Regularisation. The number of tokens (BERT wordpieces) we use to represent each document. If we use more tokens, we can represent more terms, but the vectors become denser. This number is typically between 20 to 200 per document. As a reference point, the dense BERT vector is 768 dimensions, OpenAI Embedding is 1536 dimensions, and the sparse vector is 30 dimensions.

For example, assume a 1M document corpus. Say, we use 100 sparse token ids + weights per document. Correspondingly, dense BERT vector would be 768M floats, the OpenAI Embedding would be 1.536B floats, and the sparse vector would be a maximum of 100M integers + 100M floats. This could mean a 10x reduction in memory usage, which is a huge win for large-scale systems:

| Vector Type | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|

| Dense BERT Vector | 6.144 |

| OpenAI Embedding | 12.288 |

| Sparse Vector | 1.12 |

How SPLADE works: leveraging BERT

SPLADE leverages a transformer architecture to generate sparse representations of documents and queries, enabling efficient retrieval. Let’s dive into the process.

The output logits from the transformer backbone are inputs upon which SPLADE builds. The transformer architecture can be something familiar like BERT. Rather than producing dense probability distributions, SPLADE utilizes these logits to construct sparse vectors—think of them as a distilled essence of tokens, where each dimension corresponds to a term from the vocabulary and its associated weight in the context of the given document or query.

This sparsity is critical; it mirrors the probability distributions from a typical Masked Language Modeling task but is tuned for retrieval effectiveness, emphasizing terms that are both:

- Contextually relevant: Terms that represent a document well should be given more weight.

- Discriminative across documents: Terms that a document has, and other documents don’t, should be given more weight.

The token-level distributions that you’d expect in a standard transformer model are now transformed into token-level importance scores in SPLADE. These scores reflect the significance of each term in the context of the document or query, guiding the model to allocate more weight to terms that are likely to be more meaningful for retrieval purposes.

The resulting sparse vectors are not only memory-efficient but also tailored for precise matching in the high-dimensional space of a search engine like Qdrant.

Interpreting SPLADE

A downside of dense vectors is that they are not interpretable, making it difficult to understand why a document is relevant to a query.

SPLADE importance estimation can provide insights into the ‘why’ behind a document’s relevance to a query. By shedding light on which tokens contribute most to the retrieval score, SPLADE offers some degree of interpretability alongside performance, a rare feat in the realm of neural IR systems. For engineers working on search, this transparency is invaluable.

Known limitations of SPLADE

Pooling strategy

The switch to max pooling in SPLADE improved its performance on the MS MARCO and TREC datasets. However, this indicates a potential limitation of the baseline SPLADE pooling method, suggesting that SPLADE’s performance is sensitive to the choice of pooling strategy.

Document and query Eecoder

The SPLADE model variant that uses a document encoder with max pooling but no query encoder reaches the same performance level as the prior SPLADE model. This suggests a limitation in the necessity of a query encoder, potentially affecting the efficiency of the model.

Other sparse vector methods

SPLADE is not the only method to create sparse vectors.

Essentially, sparse vectors are a superset of TF-IDF and BM25, which are the most popular text retrieval methods. In other words, you can create a sparse vector using the term frequency and inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) to reproduce the BM25 score exactly.

Additionally, attention weights from Sentence Transformers can be used to create sparse vectors. This method preserves the ability to query exact words and phrases but avoids the computational overhead of query expansion used in SPLADE.

We will cover these methods in detail in a future article.

Leveraging sparse vectors in Qdrant for hybrid search

Qdrant supports a separate index for Sparse Vectors. This enables you to use the same collection for both dense and sparse vectors. Each “Point” in Qdrant can have both dense and sparse vectors.

But let’s first take a look at how you can work with sparse vectors in Qdrant.

Practical implementation in Python

Let’s dive into how Qdrant handles sparse vectors with an example. Here is what we will cover:

Setting Up Qdrant Client: Initially, we establish a connection with Qdrant using the QdrantClient. This setup is crucial for subsequent operations.

Creating a Collection with Sparse Vector Support: In Qdrant, a collection is a container for your vectors. Here, we create a collection specifically designed to support sparse vectors. This is done using the create_collection method where we define the parameters for sparse vectors, such as setting the index configuration.

Inserting Sparse Vectors: Once the collection is set up, we can insert sparse vectors into it. This involves defining the sparse vector with its indices and values, and then upserting this point into the collection.

Querying with Sparse Vectors: To perform a search, we first prepare a query vector. This involves computing the vector from a query text and extracting its indices and values. We then use these details to construct a query against our collection.

Retrieving and Interpreting Results: The search operation returns results that include the id of the matching document, its score, and other relevant details. The score is a crucial aspect, reflecting the similarity between the query and the documents in the collection.

1. Set up

# Qdrant client setup

client = QdrantClient(":memory:")

# Define collection name

COLLECTION_NAME = "example_collection"

# Insert sparse vector into Qdrant collection

point_id = 1 # Assign a unique ID for the point

2. Create a collection with sparse vector support

client.create_collection(

collection_name=COLLECTION_NAME,

vectors_config={},

sparse_vectors_config={

"text": models.SparseVectorParams(

index=models.SparseIndexParams(

on_disk=False,

)

)

},

)

3. Insert sparse vectors

Here, we see the process of inserting a sparse vector into the Qdrant collection. This step is key to building a dataset that can be quickly retrieved in the first stage of the retrieval process, utilizing the efficiency of sparse vectors. Since this is for demonstration purposes, we insert only one point with Sparse Vector and no dense vector.

client.upsert(

collection_name=COLLECTION_NAME,

points=[

models.PointStruct(

id=point_id,

payload={}, # Add any additional payload if necessary

vector={

"text": models.SparseVector(

indices=indices.tolist(), values=values.tolist()

)

},

)

],

)

By upserting points with sparse vectors, we prepare our dataset for rapid first-stage retrieval, laying the groundwork for subsequent detailed analysis using dense vectors. Notice that we use “text” to denote the name of the sparse vector.

Those familiar with the Qdrant API will notice that the extra care taken to be consistent with the existing named vectors API – this is to make it easier to use sparse vectors in existing codebases. As always, you’re able to apply payload filters, shard keys, and other advanced features you’ve come to expect from Qdrant. To make things easier for you, the indices and values don’t have to be sorted before upsert. Qdrant will sort them when the index is persisted e.g. on disk.

4. Query with sparse vectors

We use the same process to prepare a query vector as well. This involves computing the vector from a query text and extracting its indices and values. We then use these details to construct a query against our collection.

# Preparing a query vector

query_text = "Who was Arthur Ashe?"

query_vec, query_tokens = compute_vector(query_text)

query_vec.shape

query_indices = query_vec.nonzero().numpy().flatten()

query_values = query_vec.detach().numpy()[query_indices]

In this example, we use the same model for both document and query. This is not a requirement, but it’s a simpler approach.

5. Retrieve and interpret results

After setting up the collection and inserting sparse vectors, the next critical step is retrieving and interpreting the results. This process involves executing a search query and then analyzing the returned results.

# Searching for similar documents

result = client.search(

collection_name=COLLECTION_NAME,

query_vector=models.NamedSparseVector(

name="text",

vector=models.SparseVector(

indices=query_indices,

values=query_values,

),

),

with_vectors=True,

)

result

In the above code, we execute a search against our collection using the prepared sparse vector query. The client.search method takes the collection name and the query vector as inputs. The query vector is constructed using the models.NamedSparseVector, which includes the indices and values derived from the query text. This is a crucial step in efficiently retrieving relevant documents.

ScoredPoint(

id=1,

version=0,

score=3.4292831420898438,

payload={},

vector={

"text": SparseVector(

indices=[2001, 2002, 2010, 2018, 2032, ...],

values=[

1.0660614967346191,

1.391068458557129,

0.8903818726539612,

0.2502821087837219,

...,

],

)

},

)

The result, as shown above, is a ScoredPoint object containing the ID of the retrieved document, its version, a similarity score, and the sparse vector. The score is a key element as it quantifies the similarity between the query and the document, based on their respective vectors.

To understand how this scoring works, we use the familiar dot product method:

This formula calculates the similarity score by multiplying corresponding elements of the query and document vectors and summing these products. This method is particularly effective with sparse vectors, where many elements are zero, leading to a computationally efficient process. The higher the score, the greater the similarity between the query and the document, making it a valuable metric for assessing the relevance of the retrieved documents.

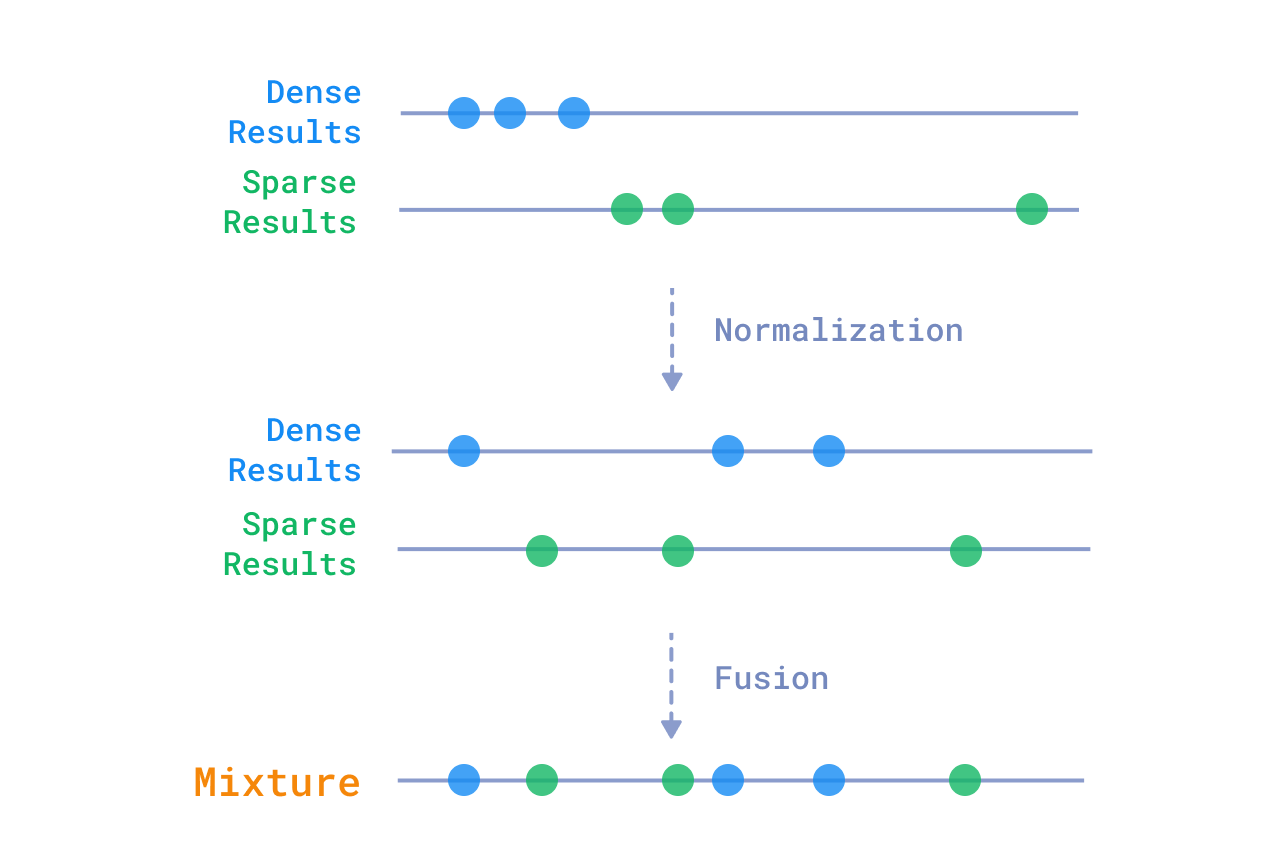

Hybrid search: combining sparse and dense vectors

By combining search results from both dense and sparse vectors, you can achieve a hybrid search that is both efficient and accurate. Results from sparse vectors will guarantee, that all results with the required keywords are returned, while dense vectors will cover the semantically similar results.

The mixture of dense and sparse results can be presented directly to the user, or used as a first stage of a two-stage retrieval process.

Let’s see how you can make a hybrid search query in Qdrant.

First, you need to create a collection with both dense and sparse vectors:

client.create_collection(

collection_name=COLLECTION_NAME,

vectors_config={

"text-dense": models.VectorParams(

size=1536, # OpenAI Embeddings

distance=models.Distance.COSINE,

)

},

sparse_vectors_config={

"text-sparse": models.SparseVectorParams(

index=models.SparseIndexParams(

on_disk=False,

)

)

},

)

Then, assuming you have upserted both dense and sparse vectors, you can query them together:

query_text = "Who was Arthur Ashe?"

# Compute sparse and dense vectors

query_indices, query_values = compute_sparse_vector(query_text)

query_dense_vector = compute_dense_vector(query_text)

client.search_batch(

collection_name=COLLECTION_NAME,

requests=[

models.SearchRequest(

vector=models.NamedVector(

name="text-dense",

vector=query_dense_vector,

),

limit=10,

),

models.SearchRequest(

vector=models.NamedSparseVector(

name="text-sparse",

vector=models.SparseVector(

indices=query_indices,

values=query_values,

),

),

limit=10,

),

],

)

The result will be a pair of result lists, one for dense and one for sparse vectors.

Having those results, there are several ways to combine them:

Mixing or fusion

You can mix the results from both dense and sparse vectors, based purely on their relative scores. This is a simple and effective approach, but it doesn’t take into account the semantic similarity between the results. Among the popular mixing methods are:

- Reciprocal Ranked Fusion (RRF)

- Relative Score Fusion (RSF)

- Distribution-Based Score Fusion (DBSF)

Relative Score Fusion

Ranx is a great library for mixing results from different sources.

Re-ranking

You can use obtained results as a first stage of a two-stage retrieval process. In the second stage, you can re-rank the results from the first stage using a more complex model, such as Cross-Encoders or services like Cohere Rerank.

And that’s it! You’ve successfully achieved hybrid search with Qdrant!

Additional resources

For those who want to dive deeper, here are the top papers on the topic most of which have code available:

- Problem Motivation: Sparse Overcomplete Word Vector Representations

- SPLADE v2: Sparse Lexical and Expansion Model for Information Retrieval

- SPLADE: Sparse Lexical and Expansion Model for First Stage Ranking

- Late Interaction - ColBERTv2: Effective and Efficient Retrieval via Lightweight Late Interaction

- SparseEmbed: Learning Sparse Lexical Representations with Contextual Embeddings for Retrieval

Why just read when you can try it out?

We’ve packed an easy-to-use Colab for you on how to make a Sparse Vector: Sparse Vectors Single Encoder Demo. Run it, tinker with it, and start seeing the magic unfold in your projects. We can’t wait to hear how you use it!

Conclusion

Alright, folks, let’s wrap it up. Better search isn’t a ’nice-to-have,’ it’s a game-changer, and Qdrant can get you there.

Got questions? Our Discord community is teeming with answers.

If you enjoyed reading this, why not sign up for our newsletter to stay ahead of the curve.

And, of course, a big thanks to you, our readers, for pushing us to make ranking better for everyone.