miniCOIL: on the Road to Usable Sparse Neural Retrieval

Evgeniya Sukhodolskaya

·May 13, 2025

Have you ever heard of sparse neural retrieval? If so, have you used it in production?

It’s a field with excellent potential – who wouldn’t want to use an approach that combines the strengths of dense and term-based text retrieval? Yet it’s not so popular. Is it due to the common curse of “What looks good on paper is not going to work in practice”??

This article describes our path towards sparse neural retrieval as it should be – lightweight term-based retrievers capable of distinguishing word meanings.

Learning from the mistakes of previous attempts, we created miniCOIL, a new sparse neural candidate to take BM25’s place in hybrid searches. We’re happy to share it with you and are awaiting your feedback.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Sparse neural retrieval is not so well known, as opposed to methods it’s based on – term-based and dense retrieval. Their weaknesses motivated this field’s development, guiding its evolution. Let’s follow its path.

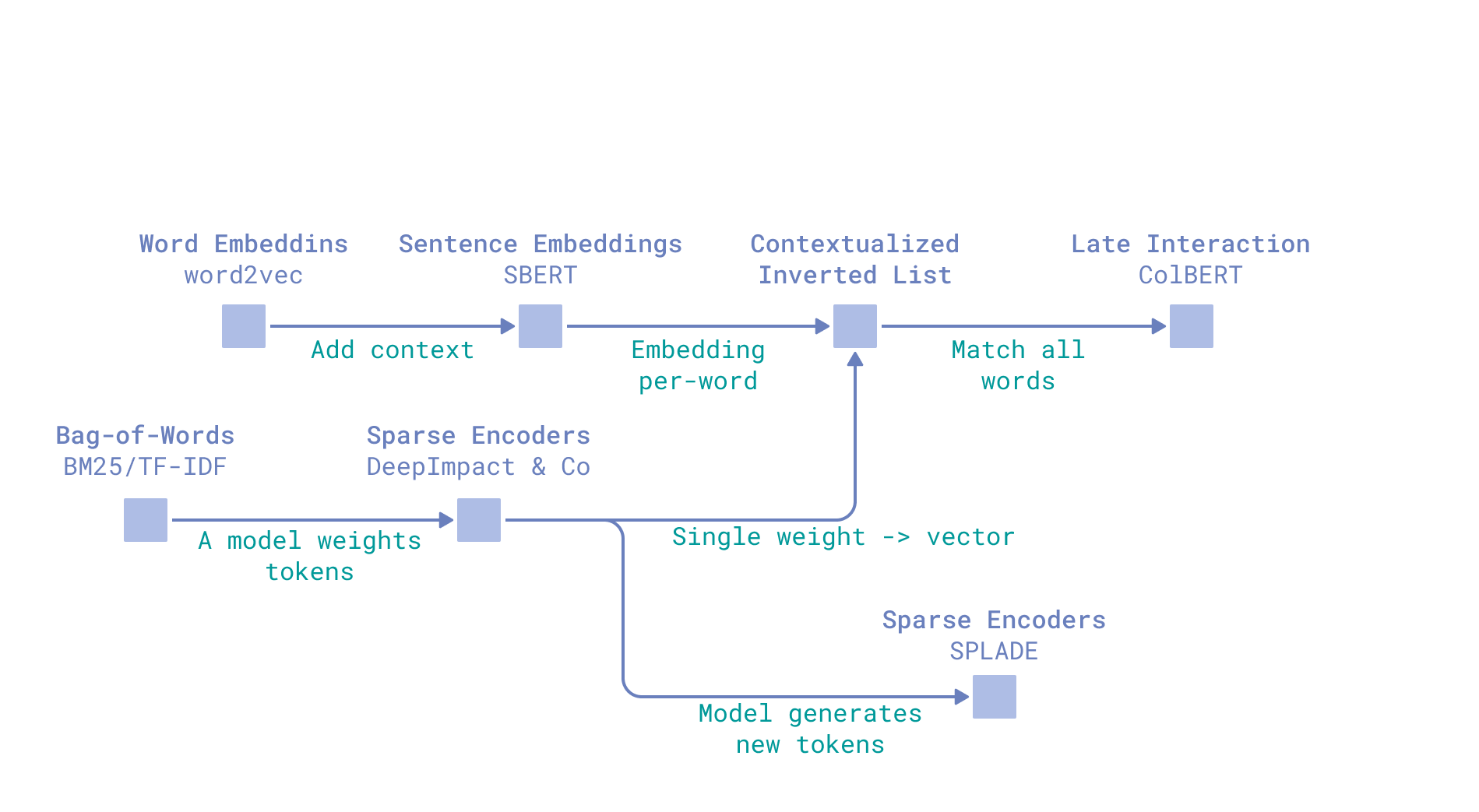

Retrievers evolution

Term-based Retrieval

Term-based retrieval usually treats text as a bag of words. These words play roles of different importance, contributing to the overall relevance score between a document and a query.

Famous BM25 estimates words’ contribution based on their:

- Importance in a particular text – Term Frequency (TF) based.

- Significance within the whole corpus – Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) based.

It also has several parameters reflecting typical text length in the corpus, the exact meaning of which you can check in our detailed breakdown of the BM25 formula.

Precisely defining word importance within a text is nontrivial.

BM25 is built on the idea that term importance can be defined statistically. This isn’t far from the truth in long texts, where frequent repetition of a certain word signals that the text is related to this concept. In very short texts – say, chunks for Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) – it’s less applicable, with TF of 0 or 1. We approached fixing it in our BM42 modification of BM25 algorithm.

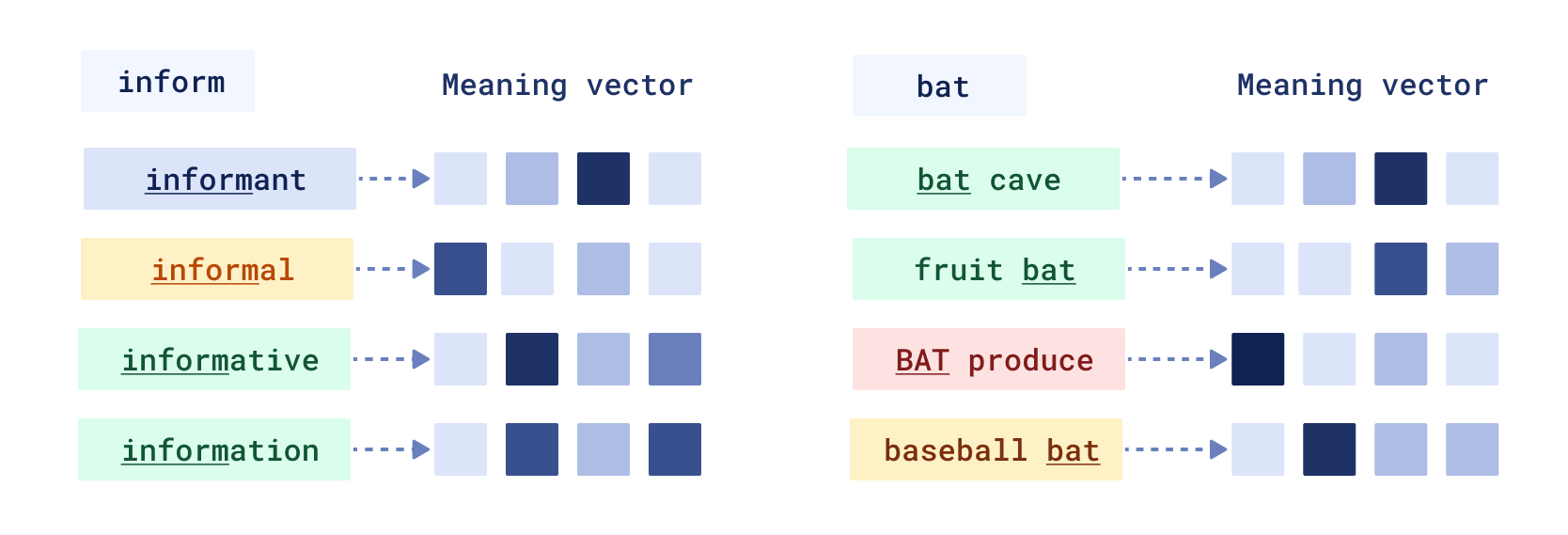

Yet there is one component of a word’s importance for retrieval, which is not considered in BM25 at all – word meaning. The same words have different meanings in different contexts, and it affects the text’s relevance. Think of “fruit bat” and “baseball bat"—the same importance in the text, different meanings.

Dense Retrieval

How to capture the meaning? Bag-of-words models like BM25 assume that words are placed in a text independently, while linguists say:

“You shall know a word by the company it keeps” - John Rupert Firth

This idea, together with the motivation to numerically express word relationships, powered the development of the second branch of retrieval – dense vectors. Transformer models with attention mechanisms solved the challenge of distinguishing word meanings within text context, making it a part of relevance matching in retrieval.

Yet dense retrieval didn’t (and can’t) become a complete replacement for term-based retrieval. Dense retrievers are capable of broad semantic similarity searches, yet they lack precision when we need results including a specific keyword.

It’s a fool’s errand – trying to make dense retrievers do exact matching, as they’re built in a paradigm where every word matches every other word semantically to some extent, and this semantic similarity depends on the training data of a particular model.

Sparse Neural Retrieval

So, on one side, we have weak control over matching, sometimes leading to too broad retrieval results, and on the other—lightweight, explainable and fast term-based retrievers like BM25, incapable of capturing semantics.

Of course, we want the best of both worlds, fused in one model, no drawbacks included. Sparse neural retrieval evolution was pushed by this desire.

- Why sparse? Term-based retrieval can operate on sparse vectors, where each word in the text is assigned a non-zero value (its importance in this text).

- Why neural? Instead of deriving an importance score for a word based on its statistics, let’s use machine learning models capable of encoding words’ meaning.

So why is it not widely used?

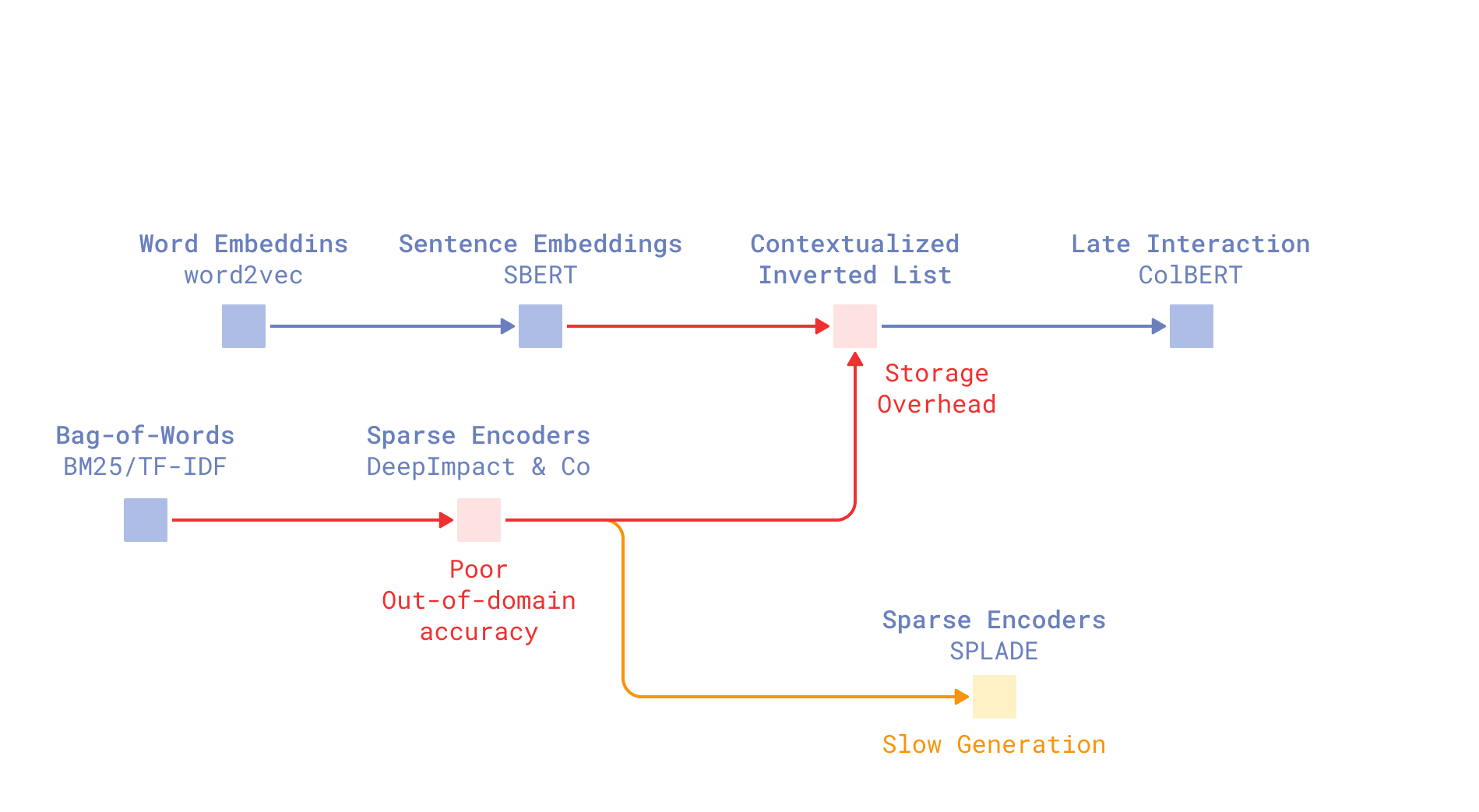

Problems of modern sparse neural retrievers

The detailed history of sparse neural retrieval makes for a whole other article. Summing a big part of it up, there were many attempts to map a word representation produced by a dense encoder to a single-valued importance score, and most of them never saw the real world outside of research papers (DeepImpact, TILDEv2, uniCOIL).

Trained end-to-end on a relevance objective, most of the sparse encoders estimated word importance well only for a particular domain. Their out-of-domain accuracy, on datasets they hadn’t “seen” during training, was worse than BM25.

The SOTA of sparse neural retrieval is SPLADE – (Sparse Lexical and Expansion Model). This model has made its way into retrieval systems - you can use SPLADE++ in Qdrant with FastEmbed.

Yet there’s a catch. The “expansion” part of SPLADE’s name refers to a technique that combats against another weakness of term-based retrieval – vocabulary mismatch. While dense encoders can successfully connect related terms like “fruit bat” and “flying fox”, term-based retrieval fails at this task.

SPLADE solves this problem by expanding documents and queries with additional fitting terms. However, it leads to SPLADE inference becoming heavy. Additionally, produced representations become not-so-sparse (so, consequently, not lightweight) and far less explainable as expansion choices are made by machine learning models.

“Big man in a suit of armor. Take that off, what are you?”

Experiments showed that SPLADE without its term expansion tells the same old story of sparse encoders — it performs worse than BM25.

Eyes on the Prize: Usable Sparse Neural Retrieval

Striving for perfection on specific benchmarks, the sparse neural retrieval field either produced models performing worse than BM25 out-of-domain(ironically, trained with BM25-based hard negatives) or models based on heavy document expansion, lowering sparsity.

To be usable in production, the minimal criteria a sparse neural retriever should meet are:

- Producing lightweight sparse representations (it’s in the name!). Inheriting the perks of term-based retrieval, it should be lightweight and simple. For broader semantic search, there are dense retrievers.

- Being better than BM25 at ranking in different domains. The goal is a term-based retriever capable of distinguishing word meanings — what BM25 can’t do — preserving BM25’s out-of-domain, time-proven performance.

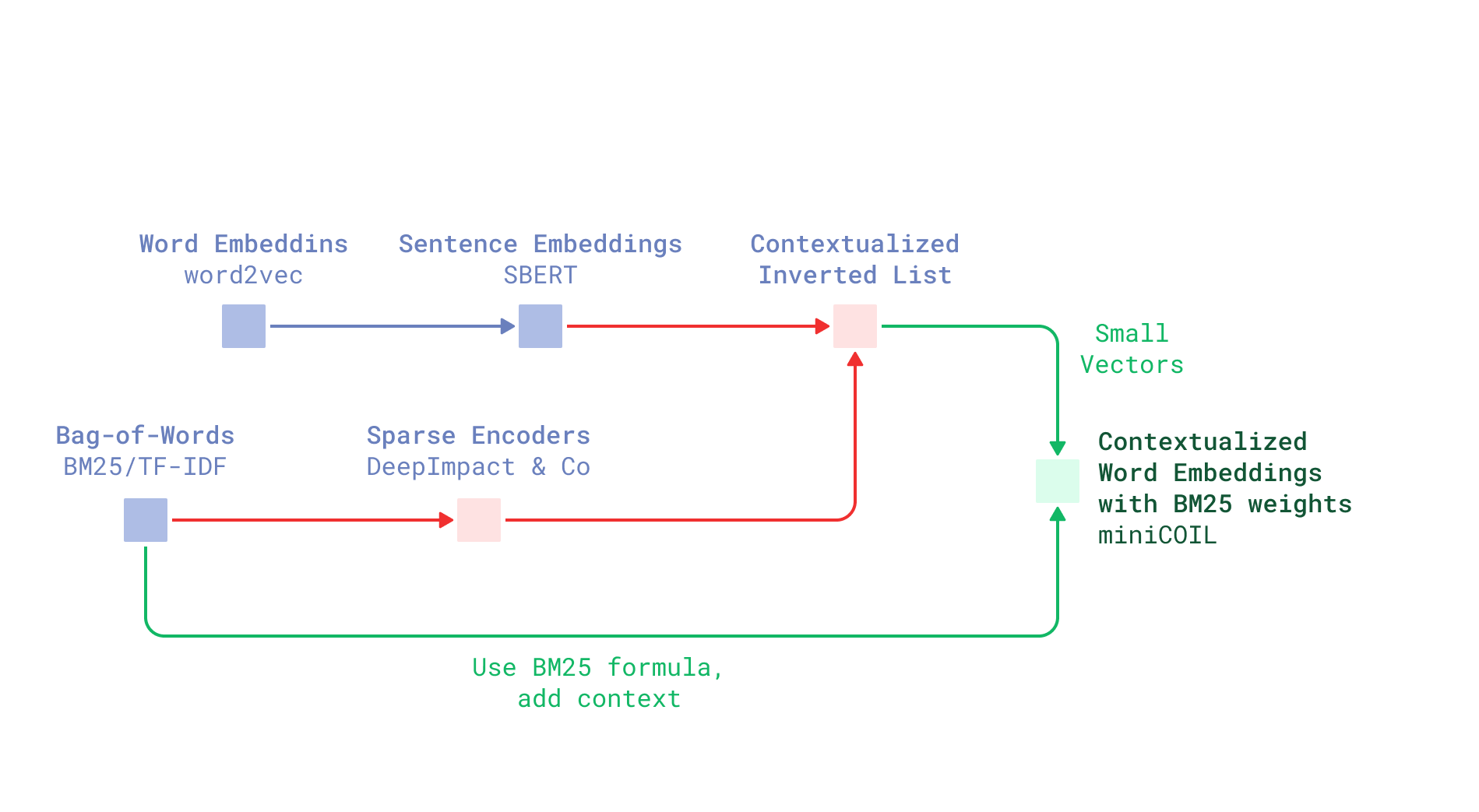

The idea behind miniCOIL

Inspired by COIL

One of the attempts in the field of Sparse Neural Retrieval — Contextualized Inverted Lists (COIL) — stands out with its approach to term weights encoding.

Instead of squishing high-dimensional token representations (usually 768-dimensional BERT embeddings) into a single number, COIL authors project them to smaller vectors of 32 dimensions. They propose storing these vectors in inverted lists of an inverted index (used in term-based retrieval) as is and comparing vector representations through dot product.

This approach captures deeper semantics, a single number simply cannot convey all the nuanced meanings a word can have.

Despite this advantage, COIL failed to gain widespread adoption for several key reasons:

- Inverted indexes are usually not designed to store vectors and perform vector operations.

- Trained end-to-end with a relevance objective on MS MARCO dataset, COIL’s performance is heavily domain-bound.

- Additionally, COIL operates on tokens, reusing BERT’s tokenizer. However, working at a word level is far better for term-based retrieval. Imagine we want to search for a “retriever” in our documentation. COIL will break it down into

re,#trie, and#ver32-dimensional vectors and match all three parts separately – not so convenient.

However, COIL representations allow distinguishing homographs, a skill BM25 lacks. The best ideas don’t start from zero. We propose an approach built on top of COIL, keeping in mind what needs fixing:

- We should abandon end-to-end training on a relevance objective to get a model performant on out-of-domain data. There is not enough data to train a model able to generalize.

- We should keep representations sparse and reusable in a classic inverted index.

- We should fix tokenization. This problem is the easiest one to solve, as it was already done in several sparse neural retrievers, and we also learned to do it in our BM42.

Standing on the Shoulders of BM25

BM25 has been a decent baseline across various domains for many years – and for a good reason. So why discard a time-proven formula?

Instead of training our sparse neural retriever to assign words’ importance scores, let’s add a semantic COIL-inspired component to BM25 formula.

Then, if we manage to capture a word’s meaning, our solution alone could work like BM25 combined with a semantically aware reranker – or, in other words:

- It could see the difference between homographs;

- When used with word stems, it could distinguish parts of speech.

Meaning component

And if our model stumbles upon a word it hasn’t “seen” during training, we can just fall back to the original BM25 formula!

Bag-of-words in 4D

COIL uses 32 values to describe one term. Do we need this many? How many words with 32 separate meanings could we name without additional research?

Yet, even if we use fewer values in COIL representations, the initial problem of dense vectors not fitting into a classical inverted index persists.

Unless… We perform a simple trick!

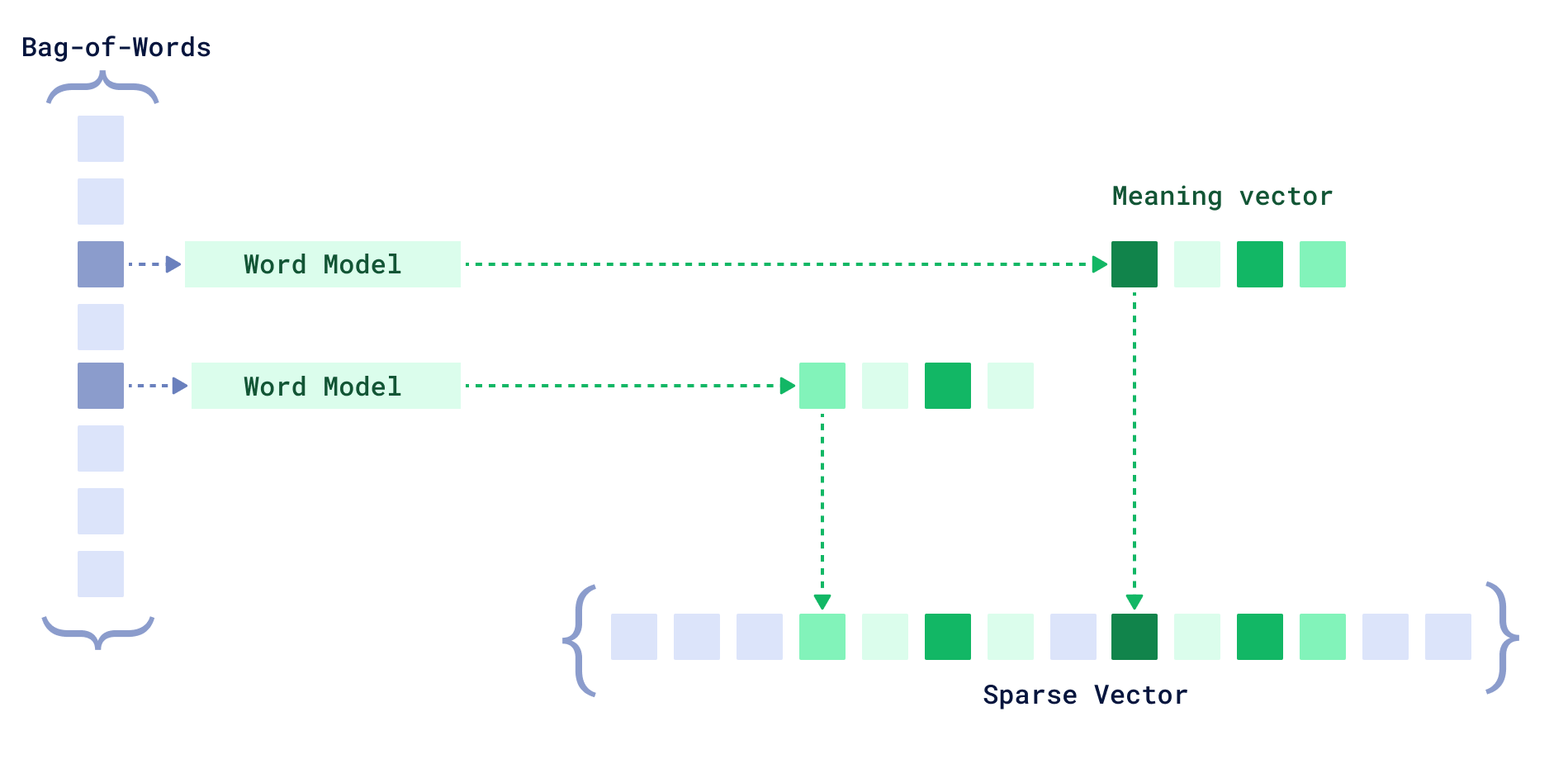

miniCOIL vectors to sparse representation

Imagine a bag-of-words sparse vector. Every word from the vocabulary takes up one cell. If the word is present in the encoded text — we assign some weight; if it isn’t — it equals zero.

If we have a mini COIL vector describing a word’s meaning, for example, in 4D semantic space, we could just dedicate 4 consecutive cells for word in the sparse vector, one cell per “meaning” dimension. If we don’t, we could fall back to a classic one-cell description with a pure BM25 score.

Such representations can be used in any standard inverted index.

Training miniCOIL

Now, we’re coming to the part where we need to somehow get this low-dimensional encapsulation of a word’s meaning – a miniCOIL vector.

We want to work smarter, not harder, and rely as much as possible on time-proven solutions. Dense encoders are good at encoding a word’s meaning in its context, so it would be convenient to reuse their output. Moreover, we could kill two birds with one stone if we wanted to add miniCOIL to hybrid search – where dense encoder inference is done regardless.

Reducing Dimensions

Dense encoder outputs are high-dimensional, so we need to perform dimensionality reduction, which should preserve the word’s meaning in context. The goal is to:

- Avoid relevance objective and dependence on labelled datasets;

- Find a target capturing spatial relations between word’s meanings;

- Use the simplest architecture possible.

Training Data

We want miniCOIL vectors to be comparable according to a word’s meaning — fruit bat and vampire bat should be closer to each other in low-dimensional vector space than to baseball bat. So, we need something to calibrate on when reducing the dimensionality of words’ contextualized representations.

It’s said that a word’s meaning is hidden in the surrounding context or, simply put, in any texts that include this word. In bigger texts, we risk the word’s meaning blending out. So, let’s work at the sentence level and assume that sentences sharing one word should cluster in a way that each cluster contains sentences where this word is used in one specific meaning.

If that’s true, we could encode various sentences with a sophisticated dense encoder and form a reusable spatial relations target for input dense encoders. It’s not a big problem to find lots of textual data containing frequently used words when we have datasets like the OpenWebText dataset, spanning the whole web. With this amount of data available, we could afford generalization and domain independence, which is hard to achieve with the relevance objective.

It’s Going to Work, I Bat

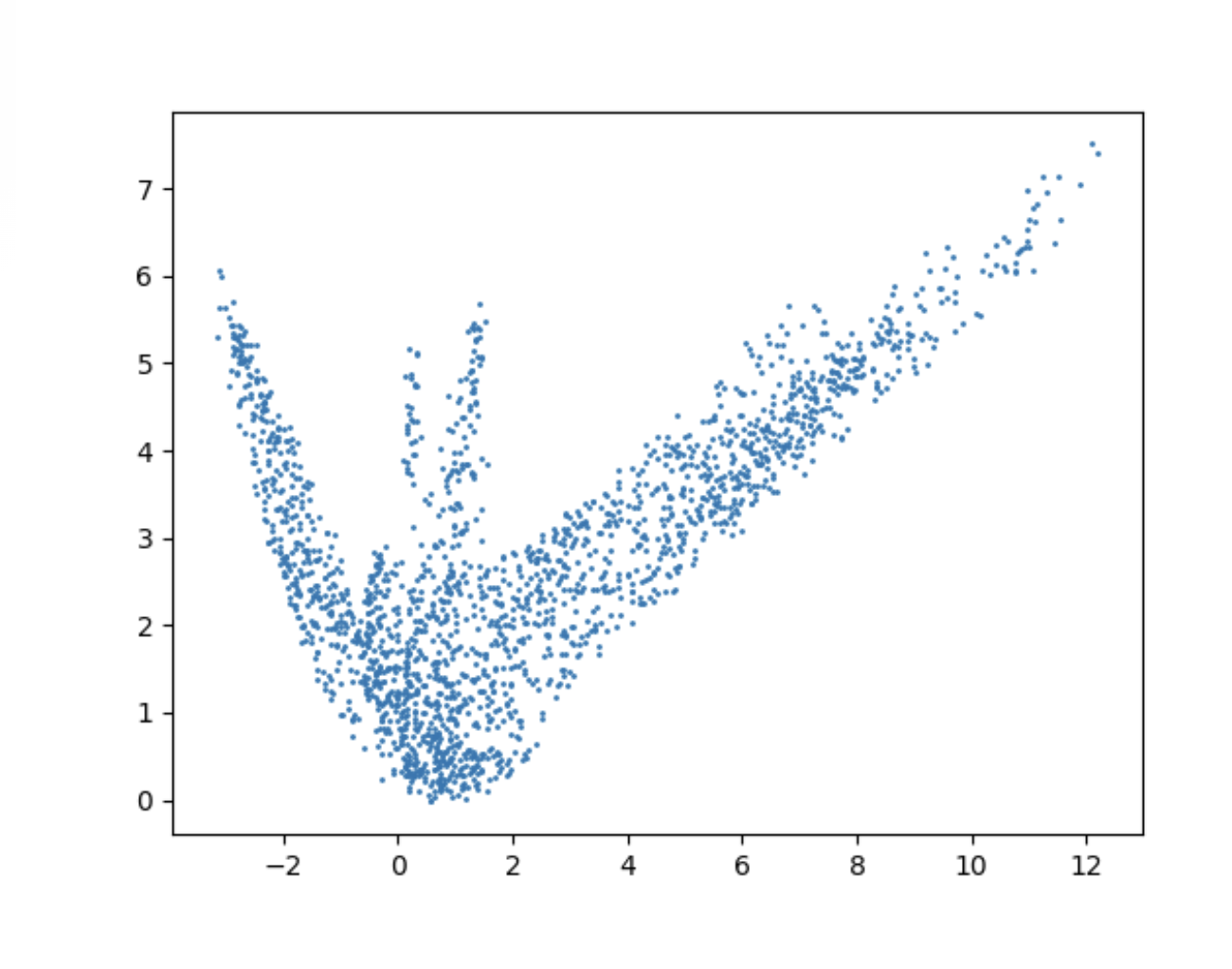

Let’s test our assumption and take a look at the word “bat”.

We took several thousand sentences with this word, which we sampled from OpenWebText dataset and vectorized with a mxbai-embed-large-v1 encoder. The goal was to check if we could distinguish any clusters containing sentences where “bat” shares the same meaning.

Sentences with “bat” in 2D.

A very important observation: Looks like a bat:)

The result had two big clusters related to “bat” as an animal and “bat” as a sports equipment, and two smaller ones related to fluttering motion and the verb used in sports. Seems like it could work!

Architecture and Training Objective

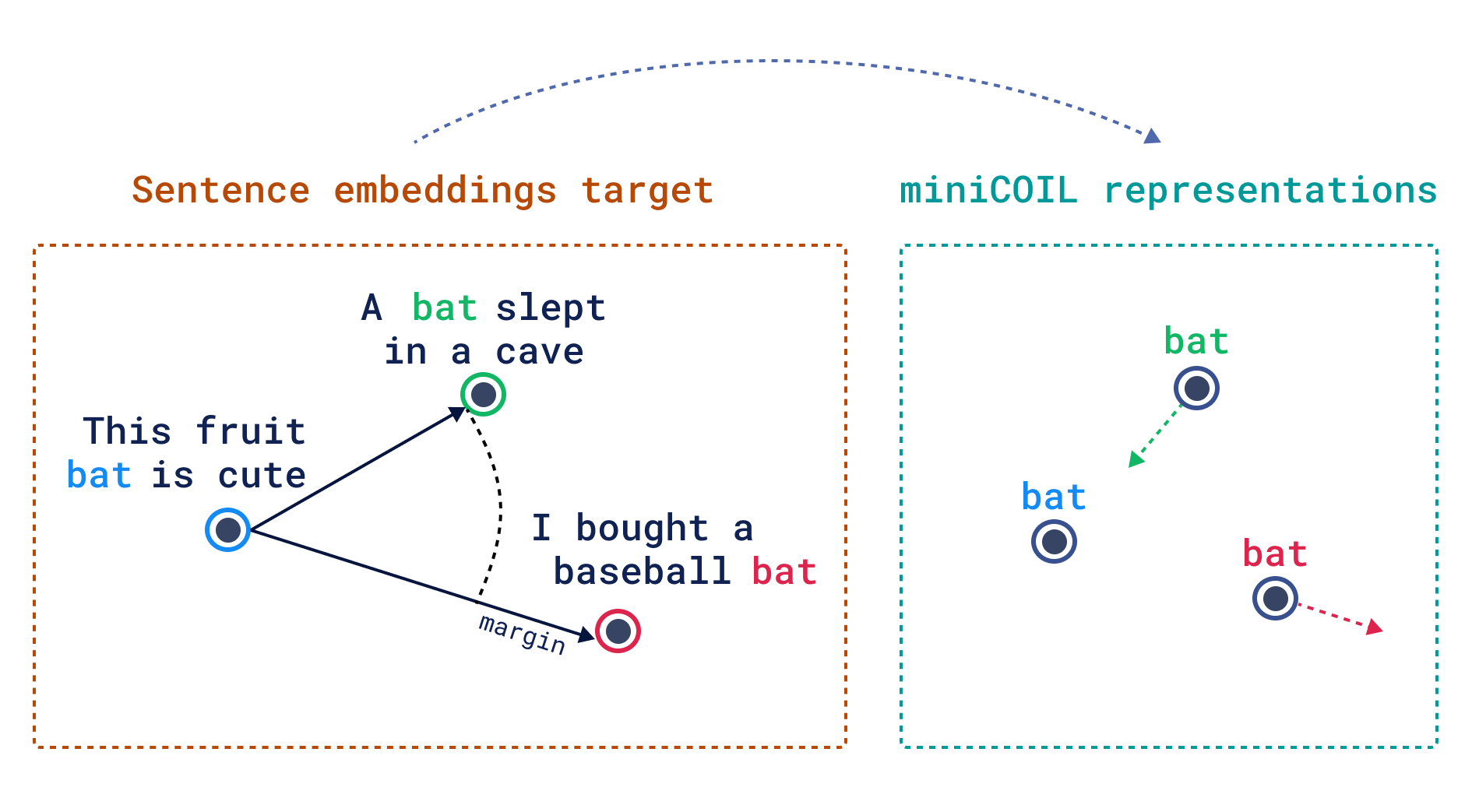

Let’s continue dealing with “bats”.

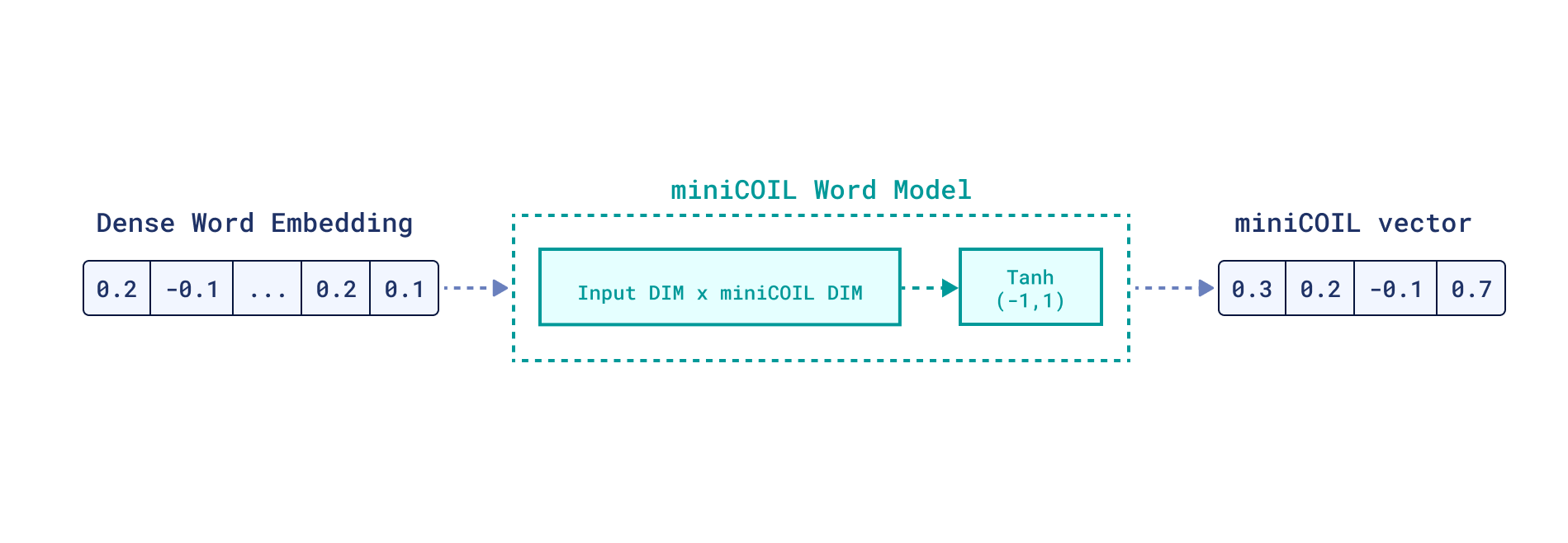

We have a training pool of sentences containing the word “bat” in different meanings. Using a dense encoder of choice, we get a contextualized embedding of “bat” from each sentence and learn to compress it into a low-dimensional miniCOIL “bat” space, guided by mxbai-embed-large-v1 sentence embeddings.

We’re dealing with only one word, so it should be enough to use just one linear layer for dimensionality reduction, with a Tanh activation on top, mapping values of compressed vectors to (-1, 1) range. The activation function choice is made to align miniCOIL representations with dense encoder ones, which are mainly compared through cosine similarity.

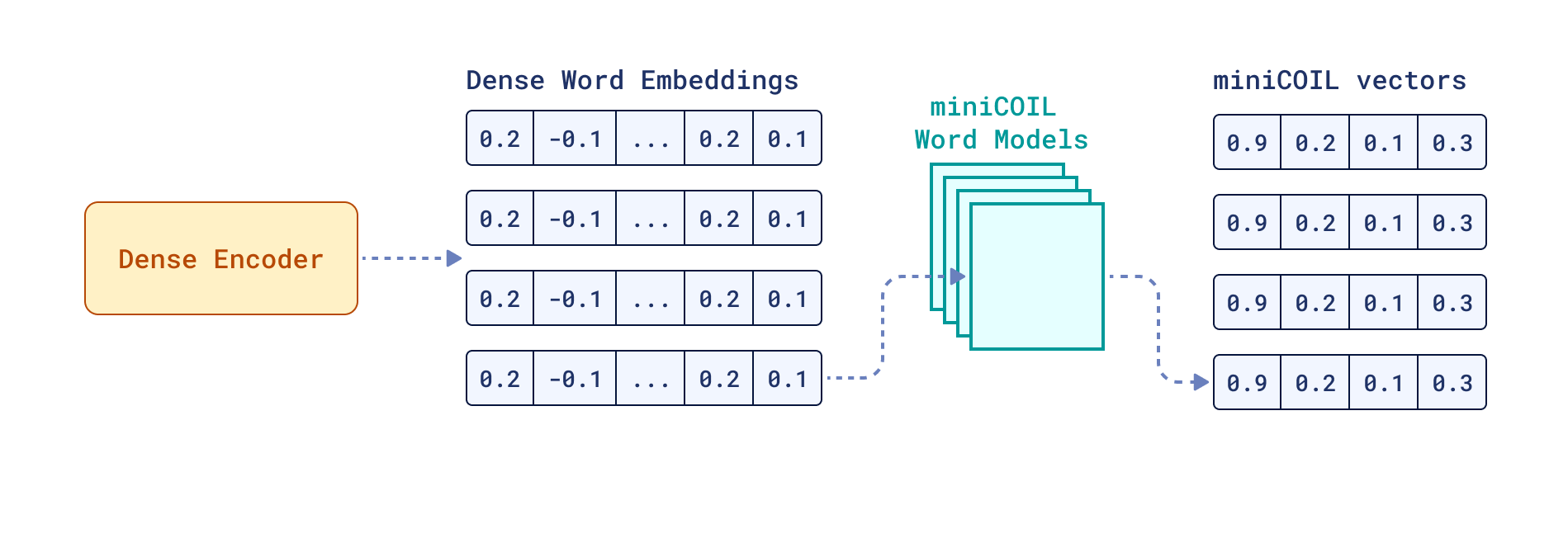

miniCOIL architecture on a word level

As a training objective, we can select the minimization of triplet loss, where triplets are picked and aligned based on distances between mxbai-embed-large-v1 sentence embeddings. We rely on the confidence (size of the margin) of mxbai-embed-large-v1 to guide our “bat” miniCOIL compression.

miniCOIL training

Eating Elephant One Bite at a Time

Now, we have the full idea of how to train miniCOIL for one word. How do we scale to a whole vocabulary?

What if we keep it simple and continue training a model per word? It has certain benefits:

- Extremely simple architecture: even one layer per word can suffice.

- Super fast and easy training process.

- Cheap and fast inference due to the simple architecture.

- Flexibility to discover and tune underperforming words.

- Flexibility to extend and shrink the vocabulary depending on the domain and use case.

Then we could train all the words we’re interested in and simply combine (stack) all models into one big miniCOIL.

miniCOIL model

Implementation Details

The code of the training approach sketched above is open-sourced in this repository.

Here are the specific characteristics of the miniCOIL model we trained based on this approach:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Input Dense Encoder | jina-embeddings-v2-small-en (512 dimensions) |

| miniCOIL Vectors Size | 4 dimensions |

| miniCOIL Vocabulary | List of 30,000 of the most common English words, cleaned of stop words and words shorter than 3 letters, taken from here. Words are stemmed to align miniCOIL with our BM25 implementation. |

| Training Data | 40 million sentences — a random subset of the OpenWebText dataset. To make triplet sampling convenient, we uploaded sentences and their mxbai-embed-large-v1 embeddings to Qdrant and built a full-text payload index on sentences with a tokenizer of type word. |

| Training Data per Word | We sample 8000 sentences per word and form triplets with a margin of at least 0.1. Additionally, we apply augmentation — take a sentence and cut out the target word plus its 1–3 neighbours. We reuse the same similarity score between original and augmented sentences for simplicity. |

| Training Parameters | Epochs: 60 Optimizer: Adam with a learning rate of 1e-4 Validation set: 20% |

Each word was trained on just one CPU, and it took approximately fifty seconds per word to train.

We included this minicoil-v1 version in the v0.7.0 release of our FastEmbed library.

You can check an example of minicoil-v1 usage with FastEmbed in the HuggingFace card.

Results

Validation Loss

Input transformer jina-embeddings-v2-small-en approximates the “role model” transformer mxbai-embed-large-v1 context relations with a (measured though triplets) quality of 83%. That means that in 17% of cases, jina-embeddings-v2-small-en will take a sentence triplet from mxbai-embed-large-v1 and embed it in a way that the negative example from the perspective of mxbai will be closer to the anchor than the positive one.

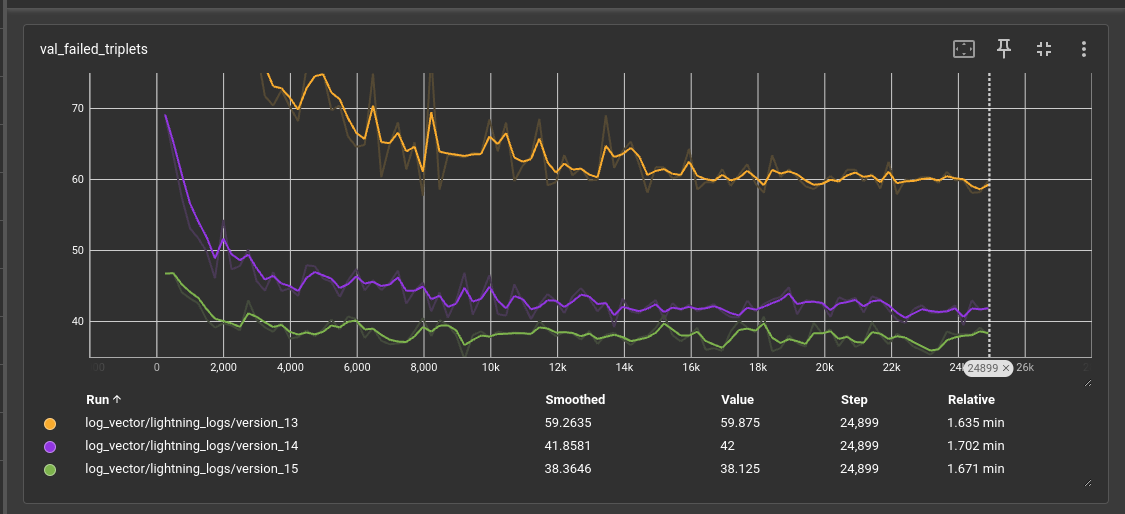

The validation loss we obtained, depending on the miniCOIL vector size (4, 8, or 16), demonstrates miniCOIL correctly distinguishing from 76% (60 failed triplets on average per batch of size 256) to 85% (38 failed triplets on average per batch of size 256) triplets respectively.

Validation loss

Benchmarking

The benchmarking code is open-sourced in this repository.

To check our 4D miniCOIL version performance in different domains, we, ironically, chose a subset of the same BEIR datasets, high benchmark values on which became an end in itself for many sparse neural retrievers. Yet the difference is that miniCOIL wasn’t trained on BEIR datasets and shouldn’t be biased towards them.

We’re testing our 4D miniCOIL model versus our BM25 implementation. BEIR datasets are indexed to Qdrant using the following parameters for both methods:

k = 1.2,b = 0.75default values recommended to use with BM25 scoring;avg_lenestimated on 50,000 documents from a respective dataset.

We compare models based on the NDCG@10 metric, as we’re interested in the ranking performance of miniCOIL compared to BM25. Both retrieve the same subset of indexed documents based on exact matches, but miniCOIL should ideally rank this subset better based on its semantics understanding.

The result on several domains we tested is the following:

| Dataset | BM25 (NDCG@10) | MiniCOIL (NDCG@10) |

|---|---|---|

| MS MARCO | 0.237 | 0.244 |

| NQ | 0.304 | 0.319 |

| Quora | 0.784 | 0.802 |

| FiQA-2018 | 0.252 | 0.257 |

| HotpotQA | 0.634 | 0.633 |

We can see miniCOIL performing slightly better than BM25 in four out of five tested domains. It shows that we’re moving in the right direction.

Key Takeaways

This article describes our attempt to make a lightweight sparse neural retriever that is able to generalize to out-of-domain data. Sparse neural retrieval has a lot of potential, and we hope to see it gain more traction.

Why is this Approach Useful?

This approach to training sparse neural retrievers:

- Doesn’t rely on a relevance objective because it is trained in a self-supervised way, so it doesn’t need labeled datasets to scale.

- Builds on the proven BM25 formula, simply adding a semantic component to it.

- Creates lightweight sparse representations that fit into a standard inverted index.

- Fully reuses the outputs of dense encoders, making it adaptable to different models. This also makes miniCOIL a cheap upgrade for hybrid search solutions.

- Uses an extremely simple model architecture, with one trainable layer per word in miniCOIL’s vocabulary. This results in very fast training and inference. Also, this word-level training makes it easy to expand miniCOIL’s vocabulary for a specific use case.

The Right Tool for the Right Job

When are miniCOIL retrievers applicable?

If you need precise term matching but BM25-based retrieval doesn’t meet your needs, ranking higher documents with words of the right form but the wrong semantical meaning.

Say you’re implementing search in your documentation. In this use case, keywords-based search prevails, but BM25 won’t account for different context-based meanings of these keywords. For example, if you’re searching for a “data point” in our documentation, you’d prefer to see “a point is a record in Qdrant” ranked higher than floating point precision, and here miniCOIL-based retrieval is an alternative to consider.

Additionally, miniCOIL fits nicely as a part of a hybrid search, as it enhances sparse retrieval without any noticeable increase in resource consumption, directly reusing contextual word representations produced by a dense encoder.

To sum up, miniCOIL should work as if BM25 understood the meaning of words and ranked documents based on this semantic knowledge. It operates only on exact matches, so if you aim for documents semantically similar to the query but expressed in different words, dense encoders are the way to go.

What’s Next?

We will continue working on improving our approach – both in-depth, searching for ways to improve the model’s quality, and in-width, extending it to various dense encoders and languages beyond English.

And we would love to share this road to usable sparse neural retrieval with you!